- Home

- Dennis McDougal

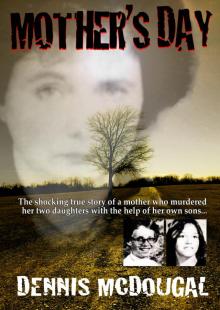

Mother's Day Page 5

Mother's Day Read online

Page 5

Though new to the bench, Superior Court Judge Charles Johnson had a long career on the periphery of the courts. A 1936 graduate of Stanford Law School, Johnson was a native Californian with a long legal career, steeped in politics. Nearly thirty years before Governor Pat Brown appointed him to the Sacramento County Superior Court in September 1963, Johnson had begun his career as a legal secretary. Later, in the 1940s, then–Attorney General Earl Warren hired him as an assistant attorney general. He had been a professor at McGeorge College of Law, a deputy to the California legislative counsel, a cabinet secretary under Governor Brown, and, most recently, a municipal court judge in northern Sacramento.

Johnson was also a staunch Democrat and a loyal ally of the governor. Some attorneys said that was the chief reason he was rewarded with the judgeship in the first place—that he had made a gift of a color TV set to the governor and good fortune followed. For all of his education and experience, Johnson was not much of a legal scholar. In fact, he had been an administrator and executive throughout his career, but had never actually practiced much in a court of law.

“He did not know the law,” said Dorfman. “But in his effort to appear brilliant, in his effort to pull it off and look professional for the jury, he invariably picked on somebody to make himself look good. He was a bigwig in the Democratic party and so was Zarick. Zarick was an older, respected attorney, and I was just a young-kid DA. The Theresa Sanders trial was an opportunity for Johnson to pick on the weak one and ally himself with the strong one. Guess who he picked on?”

In preparing Theresa’s defense, Robert Zarick worked with his nephew Marko Zarick, an aspiring trial lawyer who had just passed the bar when his uncle invited him to assist on the Sanders case. Like his uncle, Marko drank heavily and, when he did, had an eye for anything in a skirt.

“Both of them liked to drink,” said Dorfman. “Marko ended up stealing from clients, got disbarred, became a cook in a Basque restaurant up in Auburn, and died a few years ago. During the Sanders trial, the joke around the DA’s office was, ‘If she’s really pregnant, Marko did it.’”

Marko and his uncle zeroed in on Theresa’s pregnancy immediately as a surefire way to elicit sympathy from a jury. If they dressed her right and had her play up the maternal angle on the stand, they figured they had a shot at a reduced sentence at the least and maybe even an acquittal.

Marko himself was no fashion plate. He was as disheveled in the courtroom as he was in the barroom. But his uncle Robert Zarick was a dandy. He wore his hair thick and slicked straight back, not a strand out of place. According to Dorfman, the courtly old defense lawyer looked the way Moe Howard of Three Stooges fame might have looked had he worn a double-breasted gabardine suit and combed his hair back instead of letting it lie atop his head like a black mop. In the courtroom, Robert Zarick looked and acted like a force to be reckoned with.

Dorfman, who was a couple of decades younger than Zarick, knew he faced stiff competition. Still, he saw the Theresa Sanders assignment as a golden opportunity. He was convinced she had pulled the trigger on purpose and all the evidence seemed to be in his corner. If the nine-man, three-woman jury just kept its eyes open and Judge Johnson was even moderately fair in his rulings, Dorfman had a winner.

The trial began on a sticky Thursday morning when the temperature was already in the eighties before noon. In his opening statement, Dorfman told the jurors he would show that Theresa Sanders did willfully, knowingly, and with malice aforethought go to the bedroom of the Sanderses’ tiny home out near the Galt City Yard and fetch a deer rifle on the morning of July 6—a rifle that she cocked, aimed, and cold-bloodedly fired directly into Clifford Sanders’s heart.

His first witness, Buster May, recounted the tale of Mrs. Sanders, still clad in her nightgown, coming to his front door that morning, clutching her baby in her arms. He described how he found Clifford, lying on his back in a pool of blood at the back door of the little house on Elm Avenue.

After Buster stepped down, Chief Deputy Coroner Ray Thielen took the stand and picked up the tale: how Clifford’s body was taken to the morgue for autopsy; how the crime scene was sealed off and photographed; how Thielen found the murder weapon leaning against the doorjamb, along with the expended cartridge shell; and how Chief Deputy District Attorney Ed Garcia visited the crime scene and made the decision to put his agency’s own investigators on the case rather than leave it to the Galt Police Department.

Things seemed to be moving along smoothly. Dorfman got his first wake-up call the first time that he and Zarick met with Judge Johnson in chambers.

Zarick wanted to tell the jury that Clifford Sanders had once been arrested for car theft. He held up a complaint from the state of Alabama and asked to enter it into evidence as a defense exhibit. Dorfman objected long and loud. When Clifford Sanders hot-wired a car for a joyride back on the farm, he wasn’t even eighteen. Besides, a teenager’s car theft was about as far from a violent crime as jaywalking or shoplifting, said Dorfman. What was the point? What did stealing a car six or seven years ago have to do with his wife shooting him to death with a deer rifle?

Zarick shrugged. It illustrated Sanders’s bad character and showed why she had reason to be afraid of him, he explained.

And Johnson agreed.

When Dorfman exploded, waving his hands and saying that there was no legal precedent for allowing such irrelevant nonviolent criminal history into a murder trial, Johnson said he didn’t care.

“I’m looking forward to the possibility of appeal and I know the People won’t appeal and I don’t want to be overturned on appeal, so I’m going to rule in favor of the defense,” Johnson told the young deputy DA.

Dorfman recalled his reaction: he was speechless.

“What was the relevance?” Dorfman asked. “One: It happened before they were married. Two: What’s it got to do with the fact that she killed him?

“And his comment was: ‘I want the jury to know what kind of a guy he was. And I can’t make an error on the side of the defense.’ And he allowed that in. There’s no way that should have been admissible. All it did was introduce a factor into the case that had no relevance in an effort to do something that I could have never done as a lawyer: to try to show that somebody’s like a criminal because he was a criminal in the past!”

Dorfman bit his tongue, accepted the ruling, and carried on with his case. He still felt he had the upper hand.

On Friday, September 11, the second day of trial, Thielen finished testifying and was followed to the stand by Dr. Arthur Wallace, who described the autopsy results. Firearms expert David Burd was next, detailing his test of the deer rifle, which proved that it had, indeed, been the murder weapon.

Despite Judge Johnson’s peculiar ruling in chambers and an increasing tendency to overrule Dorfman and sustain Zarick in open court, Dorfman went into the weekend believing he had laid a solid foundation for a finding of guilty on the first-degree-murder charge. He returned to court on Monday, September 14 at ten A.M., recalling Ray Thielen to the stand.

Thielen, a former Army Counterintelligence Corps officer who had enrolled in law school at nights while he worked in the coroner’s office days, was as incredulous about Judge Johnson’s rulings as Dorfman. More than once, Johnson announced to witnesses, lawyers, spectators, and jury alike that he was purposely ruling more favorably for the defense than the prosecution because he did not want the California Court of Appeals overturning any conviction that came out of his courtroom.

“Charlie Johnson was a lousy judge,” said Thielen. “He’d never practiced law, and he looked up to Zarick as having knowledge of trial law. Bob Zarick was trying to show this was self-defense, and even as a first-year law student, I could see Johnson was going along with it.”

Thielen was followed to the stand by one of Clifford’s sisters, who attested to her brother’s good character. Aside from the youthful car theft back in Alabama, he had had no run-ins with the law and worked hard to support his wife and child, she

said.

Ysabel May was next, with a revelation that Dorfman believed would swing the jury to the prosecution. Before taking the stand, she had told him about a puzzling statement Theresa had made to her while the two of them waited in Ysabel’s front room for Buster to return from the death scene that morning. Theresa told her that Clifford was preparing to walk out the door, never to return, when she shot him. She said she didn’t think the gun would do that much damage.

But before Ysabel could tell the jury what she had heard, her testimony was ruled inadmissible by Judge Johnson. His reason: a recent California Supreme Court decision that required that police read a suspect his or her rights, like the more famous Miranda decision that the U.S. Supreme Court would hand down two years later. When Dorfman pointed out that Ysabel was not a police officer, Johnson waved him off. It didn’t matter, he said. She was married to a deputy.

“The judge ruled that Ysabel was actually an agent for law enforcement when Theresa came over and confessed to her because she was the deputy sheriff’s wife and [Theresa’s confession] had been made in his house!” said Thielen.

Thus, the jury heard Ysabel tell of the brutality Theresa said she suffered at the hands of her husband and how she cradled her baby in her arms while she waited for Buster’s return, but they never heard Mrs. May’s report about Theresa’s angry remark that Clifford would not get away with abandoning her.

Ysabel stepped down and a frustrated Dorfman called James Cross to the stand.

He was not there to talk about his daughter, or her relationship with Clifford. Dorfman called Theresa’s father to the stand to talk about the deer rifle.

In his quavering voice, Theresa’s increasingly frail father testified that the rifle was kept loaded in the bedroom, but that the safety was always on. Cross would not lie under oath. In order to fire the rifle, he said, his daughter would have had to click off the safety, deliberately cock the hammer, and pull the trigger—a three-step procedure that Dorfman said precluded any notion of an accidental discharge of the weapon.

After Cross left the stand, Dorfman called Thielen’s partner, Bruce Hrabak, to testify as to how he loaded Sanders’s body into the coroner’s station wagon once the autopsy was finished, and hauled it to a mortuary. Then he rested his case.

Dorfman entered ten photos of the crime scene and autopsy into evidence, along with a diagram of the house at 586 Elm Avenue drawn by Galt city surveyor Clifford Gatzert, the deer rifle, the two live and one expended cartridges, and the slug that Dr. Wallace had removed from Sanders’s heart.

Zarick began Theresa’s defense in a barely suppressed rage. He told the jury his client had been a victim of Sanders’s vicious attacks for months. Theresa wasn’t just slapped occasionally, the way some wives were, he explained. She was punched in the face. She was burned with cigarettes. Pushed to the floor and kicked like a dog. This was not a case of murder, he said. This was a case of self-preservation. This was a case of simple survival, not just for Theresa, but for her little boy, Howard, and for the unborn child she carried inside of her.

Clifford Sanders was a brute, pure and simple, Zarick thundered. He was a bully who beat his wife the way a cruel hunter might beat his hound. When his client plucked up the loaded deer rifle and aimed it at her husband that July morning, it was not out of anger or a desire for revenge or any of a host of other emotions. It was out of cold fear that he would beat her yet again. She didn’t aim to kill. The weapon went off in her untrained hands. Why else would she run to the nearest neighbor with the story that she had shot her husband in the hand? Why else would she blurt her fears that he might be hurt? Wouldn’t someone who aimed to kill simply run from the scene of the murder without worrying whether or not the victim had proper medical attention?

No, Mrs. Theresa Sanders was no murderess. Theresa Jimmie Sanders was a victim. If the jury didn’t believe it from Zarick, perhaps they would believe it from the victim herself. He called as his first witness Theresa Jimmie Sanders.

Zarick made much of the fact that Howard Sanders was barely a year old and that Theresa was three months pregnant when she was put on trial for murder. Though her pregnancy barely showed, Zarick made a point of having Theresa wear maternity clothing each day.

“He had her in a pregnancy smock from the word go, and he created a battered wife defense when none existed, Zarick did,” said Dorfman. “That this poor girl, instead of killing the man because he was leaving her, she killed him in self-defense. And none of that existed in the facts! It was just a completely fraudulent thing!”

With a cracking voice, Theresa promised to tell the truth and then tearfully entreated the jury to believe her when she told them that she had only feared for her safety and that of her babies. She had never meant to kill Clifford, she said. In fact, she had never even threatened to kill her husband before the day of the murder.

For two hours she reeled off details of the beatings she endured at the hands of Clifford Sanders.

By Tuesday, September 15, the tide seemed to be turning in Theresa’s favor.

Martha Hafner told the jury about the thin, spindly limbed little girl who used to play out back of her place on Oak Lane in Rio Linda. Mrs. Hafner spoke of the tragic dissolution of the Cross family with two sick and prematurely aging parents, one of whom literally died in her daughter’s arms. The Theresa that she had watched walking to the bus stop each morning in order to get to school on time was not a cold-blooded murderer.

After Theresa dropped out of school to marry Cliff Sanders, Mrs. Hafner rarely saw her, but she did recall for the jury one night when Theresa came to her house to hide from her husband. He beat her, she told Mrs. Hafner. He hurt her and she feared for herself and her baby.

The psychologist who carried the title “mental health counselor” for the county jail and sheriff’s department was next up. Dr. Leroy Wolter had interviewed Theresa in jail a few days after the murder and testified on the stand that, in his opinion, she was not a danger to herself or to anyone else. Again, the jury heard Theresa described as anxious, remorseful, and frightened, but not a vengeful and calculating killer. After the soft-spoken psychologist left the stand, Zarick entered Wolter’s report into evidence.

DA investigator Ellsworth Frank testified on Theresa’s behalf, too, stating for the record that his investigation had turned up no damning evidence of a woman bent on criminal intent to kill. Even the police officers who arrested her testified for the defense.

Chief Froelich took the stand and told the jury about a frightened, hysterical young woman he’d taken into custody following the shooting, how he had to get her to a doctor just to calm her down, and how concerned she seemed to be that her son be placed in good hands until her ordeal was over.

Froelich’s assistant, Captain Clyde Lee, followed the chief to the stand and told the jury about the night of June 22, when he responded to a domestic violence call at 586 Elm.

“I had had a call on her prior to this shooting because her husband had came there and abused her and took her money and threw her purse through the window and one thing and another,” Lee recalled telling the jury.

“Her and her father and the baby was there at the Elm Avenue address, and I went there and talked to them. I asked her if she wanted to sign a complaint and she said yes. But her husband, Clifford, he had left. So she signed a complaint and I went and got the warrant and then I picked the man up, out in front of the A&W Root Beer stand. I was going to take him to jail, but he wanted to talk to his wife first.

“And I said, ‘Well, now, I’ll have to see if she wants to talk to you. I don’t believe she does.’ Anyway, I contacted her, and she says, ‘Well, yes, I’ll come down and talk to him.’

“So I let them talk there while I had him in the squad car and finally she says, ‘Well, I’ll drop the charges on him. But I never want him around me again.’ And I said, ‘Well, I have the warrant. I can’t ignore this warrant. I’ll have to get the judge to withdraw it.’ So I saw our local judge and

he said if she wanted it that way, then let it go. So I did.

“But she flat out told him, ‘If you ever bother me again, I’ll kill you.’ Apparently she meant it.”

Zarick recalled James Cross and Ysabel May to the stand, this time to testify on behalf of the defense. In his halting voice, Cross backed up his daughter’s claims of abuse. Clifford did, indeed, smack her around. Ysabel, too, testified to the truth of Theresa’s plea for protection from Clifford two weeks before the shooting. It was Ysabel who advised her to see Captain Lee and swear out a warrant for her husband’s arrest.

Ysabel stepped down and Zarick rested his case.

Now Dorfman faced a dilemma. He could see sympathy swaying the nine men and three women in the jury box, but he was certain they weren’t getting the full picture. Despite the fact that Clifford was in the process of leaving the house and despite the testimony from Theresa’s own father that she had to deliberately cock the rifle and aim it before it would fire, Dorfman feared the jury was buying her battered wife defense. Dorfman smelled another motive. He believed Mrs. Sanders shot her husband out of jealousy, because he consorted with other women.

He called Dr. Wallace to the stand again as his first rebuttal witness, to reestablish for the jury how Clifford Sanders was trying to leave the house that morning and the defensive way in which he held up his hand to protect himself from the bullet.

Then he asked that Mrs. Lydia Hansen, Clifford’s older sister, take the witness stand. Zarick objected.

Mrs. Hansen was a new witness, not a rebuttal witness, he argued. If she took the stand, she could only address the points that Dorfman had made earlier, before he rested his case. The judge ordered Zarick and Dorfman into his chambers while he pondered this point of law.

“Lydia Hansen would have testified to the threats, showing a predisposition to do harm,” Dorfman said. “If Theresa expressed animosity against the guy in the past, it would certainly raise questions about this being a killing in retaliation for a beating.”

Mother's Day

Mother's Day